- Home

- Sonia Paige

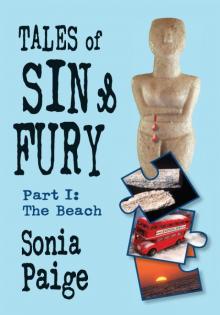

Tales of Sin & Fury, Part 1 Page 2

Tales of Sin & Fury, Part 1 Read online

Page 2

I groan. Some luck.

‘Put it this way,’ says Mandy. ‘This is the first day of the rest of your life. I know what. Got a pen, Debs?’

Debs peers in a couple of the bedside cupboards and comes up with a blue felt tip pen. The felt’s a bit squashed and woolly at the end, but it’s still moist and it makes a mark as Mandy writes the number one on the wall beside my bed and rings it with a circle. ‘Day One,’ she announces. ‘Take it a day at a time. We know. We been here before.’

Debs sits down on the bottom of my bed and twirls her pony tail slowly round her finger. She stares at my forearms below my pale blue cardigan. My right hand’s still under the covers. ‘Ain’t you skinny. I can’t see no scars.’

She’s all sharp edges and bloodless inquisitiveness. Her eyes are intelligent and piercing. I feel her long nose wanting to poke into my business. I mumble, ‘It’s a long story.’

‘Go on, then,’ says Mandy. ‘Spill the beans. We got time, here in Her Majesty’s Hilton. Debs and I are all talked out, ain’t we babes? And Debs needs some tips on how to stop slicing herself up.’

I inch my knees up under the bedclothes and hug them, there’s some comfort in that. ‘So it’s “Tell us a story” time,’ I say.

‘That’s all we got left in here,’ says Mandy. ‘They’ve taken everything else off us, ain’t they?’

‘Have you been in here long?’ I ask.

‘A few days,’ she says. ‘You don’t never stay long on this wing. Just to clean you out. Then they move you over to join the rest. Unless you come up in court first.’

I screw up my face and try to make sense of all that’s left in my brain of my arrest. The close-up views of blue serge uniforms, the stern voices, the doors closing, and the vomit… ‘They didn’t tell me,’ I say. ‘Or maybe I can’t remember.’

‘You was out like a light, mate. “We got a right alky here, chuck her into Detox.” But every alky got a story.’

A spasm zig-zags through my body and I grit my teeth.

I don’t know you. You’re like faces pressed against the glass. But you don’t want to see what’s inside.

‘So I’m Lady Muck?’ I say, ‘Why would you want to hear what happened to me?’

‘Don’t take no notice of Debs,’ says Mandy. ‘She’s just a kid. With a dirty mouth. She don’t mean it. We’re all brought down to the same level here, ain’t we? Tell you what, Debs’ll give you the low down on how she started cutting herself. I heard that one already. Then you tell us how you stopped.’

‘What?’ says Debs.

‘Go on, babes,’ says Mandy. ‘It ain’t no secret. You went to see The Evil Dead. You told me yesterday, remember?’

‘We got a deal?’ asks Debs, narrowing her eyes at me. Her mouth is set hard, not to let anything escape except verbal pellets aimed at other people. A kind of meanness hangs about her like a stale smell. ‘We got a deal?’

I shrug. Do I have a choice?

Course of least resistance. Buy time. Perhaps the world will go away. Perhaps I’ll lose consciousness and wake up next year when it’s all over.

‘Come on then,’ says Mandy. ‘“My Life with the Knife”, a true story, by Debs.’

‘Scissors,’ says Debs. ‘It was scissors the first time.’ She uses the long nail of her little finger to clean her other nails. Then she points her nose at me. I realize this is for my benefit, because Mandy’s heard it before. ‘It was a Saturday,’ she says. ‘I went to see The Evil Dead. With my big sister and her boyfriend. It wasn’t for kids, right. I was 12, but I had a new skirt and heels and that, and make-up, and I got in. It’s about these people in a cabin in the woods. All demons and people going mad and getting killed. Trees twisting theirselves round you and eyeballs popping out and chainsaws and black slime. You seen it?’

I shake my head. And from the sound of it I don’t want to.

Debs stands up, stiffens her body rigid and rolls her eyes up into her head. She twists her mouth into a parody of a smile, ‘“We’re gonna get you! We’re gonna get you!” she chants at me in a weird little girl voice. It has a grating edge like a knife scraped across a saucepan. It goes right through my head.

Mandy giggles. ‘Pack it in.’

Debs turns to her, ‘I thought it was funny too, n’all. But my sister, she’s a right big girl’s blouse. We got out of the pictures, she was shaking and looking up and down the street. It’s only a film, right? When we got back to the flats her bloke went off to talk to some mates, we were going home across the grass. She was limping, she had some stupid shoes she couldn’t walk in. I went ahead and hid behind the side of our block. I waited and when she come round the corner I stepped out and like one of them ghouls in the film I grabbed at her sudden like THAT…’

At this moment Debs’ hand springs towards my throat like an animal unleashed.

It’s a shock but I don’t flinch. I learnt at school not to react to bullies. Never show fear. And anyway I’m too far gone to care. I sit tight and stare back at her.

‘… It was a joke,’ says Debs. She opens her mouth wide and lets out a roar of demonic laughter.

‘Some joke,’ says Mandy.

Debs lets her hand drop from my throat and stops laughing. ‘Well, I didn’t know, did I? How she’d go?’

‘What happened?’ I ask.

‘My sister, right,’ says Debs, ‘she sort of exploded into bits like a balloon. Shrieking and panting like someone having a good time. Shaking. Yelping like a cat that got trod on.’

‘Sounds like she was having a fit,’ I say. I put my hand up to my head again. My left hand. Keep the right hand hidden. I take the weight of my head. Maybe something can stop the spinning.

‘A fit, right, that’s what my mum said, when I got my sister upstairs to the flat. Hysterics. Going on like that, “WA – WA – WA – WA – WA”.’ As she imitates her sister, Debs’ arms oscillate and her pony tail judders and her lips vibrate. It would be funny if it wasn’t painful. ‘Daft sod my sister, my Mum slapped her round the face but she didn’t stop. “WA – WA – WA…”’ Debs does the shaking again like a crazy kettle over-boiling.

‘Your poor fucking sister,’ said Mandy, ‘What you done to her…’

‘My sister kept pointing at me,’ Debs says, ‘and they sussed it was all down to me. They were well pissed off. They tried to give her water to drink but she knocked it on the floor.

‘My dad turned on me, “Hope you’re pleased with what you done to your sister, you little monster.” She was always his favourite.

‘He took his belt off. “You’re not too old to learn the hard way.” He grabbed me and tried to put me over his knee like I was a kid. My mum didn’t do nothing to stop him. I fought back. Fuck him. Put his filthy fucking hands on me. I got away, right, and I ran into our bedroom and I locked the fucking door. My sister was still doing her nut, I could hear her. I felt like I was bursting, like I had to do something. I opened my sister’s drawer. I found a pair of nail scissors. The first line I made it didn’t do nothing. But then I did it again. Nice and slow, so I could see the skin ripping.’ Debs holds out an arm to show me. In the criss-cross of thin red scars she directs me to a particular one. Almost with pride.

‘Silly cow,’ says Mandy. ‘You wasn’t hurting no-one but yourself.’

Debs strokes her arm. ‘You don’t get it, do you? When the blood started coming, I felt better. It blotted out the other stuff. That’s how it goes. Works every time.’

There is a silence. Like a nasty taste I remember how bad you have to feel about yourself for the sight of your own blood to be a relief. I look at her small tight mouth and there is just a quiver on the upper lip. It hurts, all ways round, but she’s not going to let on.

‘Works every time,’ she spits out again.

Then Mandy says, ‘Until the next time. If you haven’t bled to death.’

‘I know when to stop.’

‘That’s what they all say.’

‘You can talk,’ say

s Debs. ‘If you’re so know-it-all, how come you’re doing heroin?’

‘Leave me out of this,’ says Mandy. ‘Now you gonna hear from Corinne here how she stopped all that hanky panky with knives.’ She turns to me, ‘Over to you, babe. Hope you’re gonna cheer us up.’

I shut my eyes. ‘I’ve never talked about this stuff to anyone.’ Perhaps when I open them all this will be gone.

‘That’s OK,’ says Mandy. ‘In here don’t count. We’re doing time, ain’t we? We’ll never meet on the out. In here’s a different world, init, Debs? Go on, Corinne. Never know, you might even feel better after.’

I open my eyes. It’s all still there. Same cell. Same smell of hot dirt and sweat. Same flickering fluorescent light that irritates overloaded switches inside my head. Same two women by my bed, looking at me. ‘OK, I’ll tell you why I never cut myself again.’

It can’t make me feel worse than I already do. How stupid do I feel to tell them it was because of a man I cut myself twenty years ago. And here I am going through hell again. Because of another man. Back at rock bottom. Back in this grey netherworld, transparent as a wraith. I can’t blame the people whose hands slipped against mine as I fell into the abyss. The abyss is inside me.

‘OK,’ I say again, ‘I’ll tell you what happened.’ Twenty years ago. I’ll do anything not to think about what happened yesterday. Maybe I could hitch a ride on the story and end up somewhere else. Maybe I could weave my own magic carpet to escape from here.

I take a deep breath.

Mandy exchanges glances with Debs. ‘Oi, quit stalling.’

‘Talking’s difficult,’ I tell her. ‘I need a drink.’

‘Get started,’ says Mandy. ‘It’ll take your mind off of it.’

I cough and retch and put my hand over my mouth and rummage in the bed for that bit of tissue. They’re still looking at me, waiting. Eventually I say, ‘It was back in 1971.’

‘What? I was only seven then,’ says Mandy, ‘You don’t look that old, mate.’

‘I was only just born,’ echoes Debs.

‘I was twenty two,’ I tell them, ‘and I was in love.’

‘That’s new,’ says Mandy. ‘Nice, was he? Handsome?’

Handsome? Not really. Tall and dark… but not handsome. Twenty years later, his face is still scorched into my retinas. Skulking. Glowering. He didn’t need looks for what he did. Just charisma like a razor. He sucked all the love out of me. He squeezed out my confidence like the juice from an orange.

I dab with my fingers at a mark on my blue cardigan. I must have been sick on it at some point. If we could rub out memories. ‘I don’t know if you’d say nice,’ I tell them. ‘But when he ended it, in the summer of ’71, I felt so raw inside I needed a knife to show it on the outside. A serrated knife with a brown wooden handle.’ Debs’ hawk eyes are scouring my lower arms. ‘The scar isn’t on my arms,’ I tell her, ‘Mandy knows where it is.’

But I’m not going to show you. So unpeel your eyes. Back off.

‘Friends tried to patch me up. But I couldn’t pretend that life goes on. I went back to the cottage in Dorset where I’d been with him, and waited for him. I waited for months.’

‘Did he have a name, this bloke?’ asks Debs.

I’m scared to say it, even so long after. As if speaking it out loud could summon him back. I steel myself: ‘Hayden,’ I say.

‘There, that wasn’t so hard,’ says Mandy. ‘So, where were you… In some cottage…?’

‘Yes,’ I carry on. ‘In December ’71, nearly twenty years ago, there I was sunk in that threadbare chintz armchair. Where he used to sit. Hayden.’ Saying his name out loud again is strange. Hearing my voice speaking in sentences is strange. But the words seem to come stumbling out, one following the other. ‘I was waiting for him to come back. Shivering in front of the fire where he used to warm his hands. Logs spluttering in the old-fashioned black iron hearth. But nothing could drive the cold out of my bones.’

I always thought he would come back. On the arm of the chair was my diary. Where I’d written it all. The blue cover with words and pictures pasted on it, from the good times of our summer together. The edges of the pictures were curling. Our love was unpeeling.

‘I looked into the fire, and that was when I realized I had to go to Greece.’

‘Greece?’ says Debs. ‘Whassat for?’

I stop and think. ‘I don’t think I knew at the time. Perhaps it was the Greek myths I read as a child. I didn’t know why or how, but I knew I had to go. And I did. One day I started walking and left everything behind.’

All the clothes I wore when I knew him. My blue cord jeans with the patchwork flares I’d sewn in. My embroidered blouse with the ribbon he used to untie. The books. Even my diary. That diary. I left that behind too. If I could see the diary again, perhaps I could understand what happened.

‘So did ya walk there?’ asks Debs.

‘I walked the first bit. Then I hitched. I’d saved some money. Got trains. I worked here and there. I kept going ’till I got to Greece. It had always been my dream. I buried my nose in the sand and the sun melted me and joined me together again. Healing the wound.’

‘Lucky sod,’ says Mandy.

‘I been in the sun,’ says Debs, ‘and it didn’t make no difference to me.’

‘I was there for weeks, months. Camping by the sea with these two guys. It’s because of them that I never cut myself again.’

‘Two? That’s naughty. Let’s have it.’

I look at these two women I don’t know. ‘Why am I telling you this?’

‘Take it this way,’ says Mandy, ‘We ain’t going nowhere for a couple of weeks. ’Till we done the detox. We get out of this room two hours a day if we’re lucky. We’re out of tobacco. The food’s crap. There’s no TV. Shoot.’

I feel cornered. My head is pounding and I don’t feel strong enough to argue. I struggle with my left hand to prop a pillow behind my back. Mandy comes round to help and whispers in my ear, ‘Go for it, girl.’

A smile passes between us, we kind of make half of it each, and I start.

‘We were camping on an island. On the ferry going there I realized why it had to be Greece. It was around Easter 1972. I was sitting on a bench on deck with my hair blowing, the light so bright it hurt your eyes. “Luminous,” Henry Miller called it.’

‘Who’s he?’ asks Debs.

‘I was reading his book about Greece.’

‘What’s he got to do with it?’ asks Debs.

The pain in my head makes me wince. So I’m going to be cross-examined too. ‘Look’, I say, ‘It’s hard enough for me to get any bloody words out. If you want me to tell you what happened, I have to remember it my way. I have to go back and picture it all again. Every little thing, take it or leave it.’

‘We got you,’ says Mandy. ‘Get on with it, then.’

‘So, I was reading Henry Miller. Macho man, spilling his thoughts onto the page like he was the last big spender. Weaving words about his impressions. Travelling through that shimmering landscape. The rocks are mad, he said, mad with history. I was soaking it all up. Putting distance between myself and what I’d been through. Trying to leave my troubles behind. Trying to escape to those bare mountains rising out of the deep blue, the islands we were passing. The dazzling sun and the dry air. I was beginning to feel that nothing could touch me, the wind was too clean and the food from the Tourist Class cafeteria smelt too sweet, and the lavatories were too shitawful.’

‘Like in here,’ says Mandy.

‘Worse,’ I say. ‘They had a piece of flat ceramic on the floor with a hole in the middle. People called them “shit-and-run”. You had to crouch over. And usually the people before you had missed the hole and there were piles of …’

‘I feel sick,’ says Debs. ‘I liked it better on deck.’

I backtrack. ‘OK. I was sitting between two English men. I looked over their shoulders. One of them was reading in a newspaper about torture in Northern

Ireland. The other was reading a colour supplement. Something about the silent majority and everyone in England sinking into a coma. I remember thinking, I’ve got to get away from these people, from everything to do with England. Away from everything I know. Away from myself. I need fresh air.

‘I moved down the deck and the only free seat was next to a boy with big ears who turned out to be American. He greeted me, “Hi! Are you German? English?” He was lanky, with sandals and a rucksack.

‘My spirits sank. “English,” I said.

‘“I was just in London,” he told me. “Did you see the Tutankhamun show at the British Museum?”

‘I hadn’t, but that didn’t stop him talking. “Do you know if that’s the island in that film with Melina Mercouri?” He started telling me the plot of the film. “Home’s not like this, that’s for sure.” Then he took out a small brown notebook. On the cover I could see he had written his name “Walt Wyman”. And underneath, “Portrait of the Artist as a Traveller”. He opened it and started writing. I could see over his shoulder. His handwriting was tiny, cramped in tight rows. I watched, wondering what he was recording that was so important to him.’

Like that diary I kept during the last year in England, pouring out my troubles as my life fell apart. That diary, still lying in the empty cottage where I’d left it, full of secrets that mattered to no-one. Dismal to think about the millions of words people scrawl out the world over, just like him. Just like me. Why do we believe that what we think and feel is worth writing down? Are we ever going to read it again? Do we expect other people to read it?

I can feel my body sinking back into the pillow with the hopelessness of it. ‘For what was he writing?’ I mutter. ‘It made me feel tired.’ I put my hand over my eyes.

‘Perhaps it made him feel better,’ says Mandy, ‘Like talking. Get it off your chest.’

‘I couldn’t see it that way then,’ I reply. I drop my hand and look down at my empty boots on the floor. ‘Perhaps I envied that American. After I left Dorset, I could never write anything, never finish anything. As if it was all locked up in that cottage along with the hope of seeing Hayden again. I felt that anything I wrote would be useless. Without him the words seized up.

Tales of Sin & Fury, Part 1

Tales of Sin & Fury, Part 1